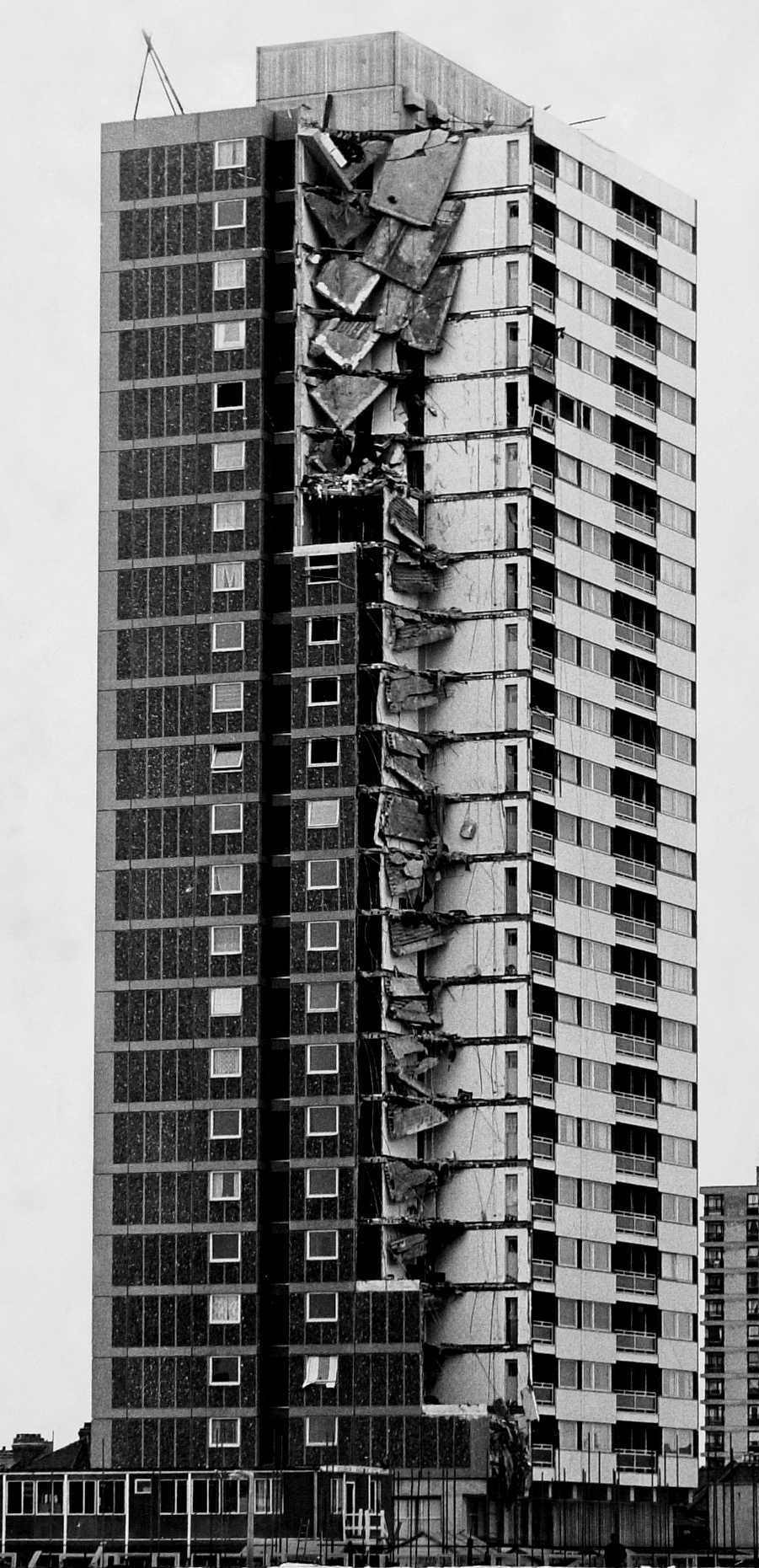

House of CardsOn 16th May, 1968, Mrs Ivy Hodge, a council tenant in a block of flats called Ronan Point in east London, wandered into the kitchen of her 18th floor flat. She leaned over her cooker and struck a match. Instantly, an explosion blew out the pre-cast concrete panels which formed the side of the building. The entire end of the block collapsed like a house of cards. Mrs. Hodge survived, but four others died.

It was modern architecture’s Titanic, and spelled the end of the high-rise as a viable solution to the post-war housing crisis as well as plunging modern architecture and the architectural profession to a low level of public esteem.

Over 200 feet tall and containing 110 flats, Ronan Point was assembled from pre-fabricated concrete panels lifted into position by crane and held together by bolts. It was a ‘system-built’ block- an easily assembled structure more like a giant meccano set than a work of architecture. But system-built blocks were an easy way to build lots of houses quickly, and in the year previous to the disaster, 470,000 new flats and houses had been built- the largest number recorded.

The sheer scale of this production meant that architects were often not directly involved in the production of these blocks- this was considered more of an engineer’s job. But since World War Two, high-rises had become virtually synonymous with the Modern Movement, and their fall from grace inevitably impacted on the public’s opinion of Modernism in general.

The Only Way Is Up

Ronan Point and other system-builds had as much to do with politics as with architecture. Municipal leaders saw high-density housing as a means of preventing population drain: the more people they governed, the stronger their city’s position would be vis-a-vis Whitehall. And since the 1956 Housing Act introduced subsidies to local councils for every floor they built over five storeys, there existed a clear financial incentive to build high.

Ronan Point was in effect a visible symbol of post-war political rhetoric. When people saw these blocks going up quickly, they could be sure that whichever government was in power was striving to fulfil its promises to tackle the housing problem.

Unfortunately, quality control, certainly at Ronan Point, was almost completely absent. When local architect Sam Webb examined joints within the structure he found them to be filled with newspapers rather than concrete. Instead of the walls resting on a continuous bed of mortar they rested on levelling bolts, two per panel, and rainwater was allowed to seep into the joints. The whole weight of the building was being taken on these bolts, which were under enormous pressure as a result. This caused the load bearing concrete wall panels to crack.

The Backlash Begins

Ronan Point was rebuilt, but eventually demolished in 1986. The entire Freemason estate has now been replaced with two-storey terraces. Politically, Ronan Point also undermined careers of several prominent local and national politicians, as the press began to investigate connections between them and companies which specialised in system-built tower blocks. But the effect of Ronan Point’s collapse on the reputation of the Modern Movement was even more profound.

Since World War Two, modernism had been the vehicle by which much of Britain was rebuilt. New Towns like Cumbernauld, and housing estates like Alton West at Poehampton and Keeling House had promised to solve Britain’s chronic urban problems and contribute to a better, modern, country.

Now a flimsy tower block (which would have horrified and appalled Le Corbusier) had started a backlash against Modernist architecture which would tarnish the Movement in Britain for the best part of the next thirty years.

Newham Council

Construction Date:

1968 (demolished 1986)

Location:

Newham, London